My Cowbojsky Boty

Or, "How to Own it When You Don't Own It."

Writing by Barbara Adler

Illustrations by Brit Bachmann

Photography by Barbara Adler and Ash Tanasiychuk

Videos by Ash Tanasiychuk

“A cowboy without a horse just wants to get to where they’re going.”

This summer, I picked up that piece of cowboy philosophy by wandering – horseless — through the Czech countryside in a pair of foot-shredding cowboy boots. I know: there are at least two things that are “off” about this picture. The Czech Republic is not for cowboys, it is for beer drinkers and young romantics who like haunted castles. Cowboy boots are not for hiking, they are for Albertans and alt-roots bands that need a ‘look’ for their photo-shoot. And yet, I spent my summer collecting blisters in the name of Klasika, the year-long, multidisciplinary art project which I am introducing here.

Klasika uses Czech tramping and Czech woodcraft culture to ask how intentional hybridity, cultural borrowing, fiction and thievery could transform our environmental imaginations. Blending musical theatre, popular song, film and artful outdoor recreation, Klasika uses various tactics, including costumed hiking, to ask: how do we use art to survive the wholesale blanding of both our landscapes and our cultural lives?

On an even more basic level, the project also asks: how does a bookish artist from the city buy cowboy boots at an American farm supply store without feeling like a total poser? Or, what do you say to the person who confronts you with absolute proof of your inauthenticity?

Barb the Boot Fitter: “…You want cowboy boots for what?” Me: “…for hiking. I will be wearing cowboy boots and dressing like a cowboy and hiking around the Czech Republic.”

Barb the Boot Fitter: “…”

Me: “It’s an art project.”

Barb the Boot Fitter: “You know, we do have hiking boots. ”

Me: “I’m in art school.”

Barb the Boot Fitter: “So…someone is giving you marks for this?

Barb didn’t soften until I told her about the real connection between Czechs and cowboys, which goes something like this:

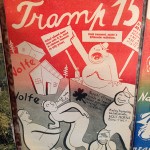

For just about one hundred years, starting in the early 1910s, thousands of Czechs participated in a pair of related counter-culture movements called tramping and woodcraft. These cultures embraced a wide span of activities, but both took inspiration from fantasies of the Wild West, adapting and appropriating myths of the American frontier into the Bohemian countryside. Simply put, there was a time in the Czech Republic when it was cool — if you were ‘in’ on it — to dress up like a cowboy, a pioneer, or an “Indian”, and wander around the forest.

Some tramps created settlements of cabins called “osadas”, while others packed the bare minimum and went on “vandrs” where they slept under the stars, or in simple cabins, left purposely unlocked for strangers. Woodcrafters formed “tribes”, and organized nature education programs for youth, where feats of learning were rewarded with “eagle feathers”. Tramps and woodcrafters had their own magazines, bands and sports leagues. A tramp’s nickname or a woodcrafter’s “Indian” name unlocked an alternative identity, which came alive through friendships in the forest.

Why this is more than just a pitch for the next Wes Anderson film…

The Czech Republic is a small country with few landscapes left that could qualify as ‘untouched’ by human settlement. The hundred years or so covered by this history saw its spaces further restricted by different political regimes and occupations. The mythical expanses of America became a code for freedom, first posed in everyday opposition to the bourgeoisie moral strictures of the Hapsburg Empire, then Nazi occupation and finally, the Soviet-imposed Communist regime.

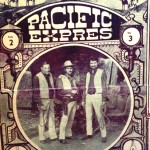

As cheap forms of recreation, tramping and woodcraft had the potential to carve out little pockets of freedom everywhere. You didn’t even need a car. Trains could take you directly to the forests and the rivers, and once you were there, the landscape could be something you created through your own imaginative acts. So, place names pulled from Western movies and novels could give the cultivated Czech hills a new expansiveness and inject something wild into long-tamed woods. Stories came to life: Sázava river became ‘Gold River’, in honor of Jack London’s gold rush tales. An old quarry site became “Amerika” because it resembled a (tiny) Grand Canyon. Pioneer settlements bore names like “Walden”, “Dakota”, and even “Toronto”. Tramps snatched American folk, country and blues classics and translated them for Czech audiences, sometimes rendering the originals nearly unrecognizable; something new. They wrote their own songs too, about rambling, Texas gunfights and enthusiastic whiskey drinking.

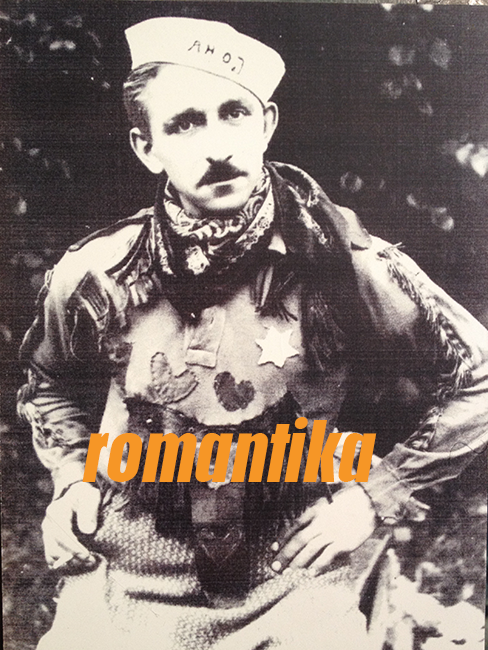

To this day, you can see totem poles and ‘pioneer’ log cabins along the rivers and in the forests; some Czechs still sing songs about cowboys and hobos; there are still tramp sheriffs, Czech Pony Express riders and woodcrafters with the skill and materials needed to build an ‘authentic’ Czech-Plains tipi. Tramps and woodcrafters alike make principled stands against Gortex and other high-tech gear, preferring to pick clothing and equipment that evokes a kind of picturesque ‘romantika’ in the woods.

First Sheriff of Osada Dashwood, circa 1928 from the Permanent Exhibition: Tramping a priroda dolniho Posazavi Regional Museum, Jilove u Prahy . Photo by Barbara Adler

So where’s the ‘real thing’? And how do I bring it home?

If you live in the Pacific Northwest, you’ve probably noticed that ‘Western’ imagery has been making the rounds through our own streets for several years now. Lumberjack plaids roam the coffee bars, leather and canvas backpacks enlist in University classes, re-claimed wood adorns nearly every microbrewery/taco commissary/boutique butcher shop and general store this side of the suburbs. The frontier and its material goods are currently a hot commodity.

When Barb the Boot Fitter sold me my boots, she set me on a ride through some of the trickier terrains of cultural appropriation and commodification. Klasika will tell the story of a group of artists in Vancouver, who try to adapt an underground Czech youth movement to their own context in Vancouver. As we build the show, we will be experimenting with practices borrowed, stolen, adapted and hybridized from the Czech context.

Some aspects of the Czech practices make sense to adapt to a Canadian context, and others do not. It’s obvious that uncritically reproducing the Czech fascination with Native American culture would be harmful and irresponsible in a Canadian context. But questions like, “what am I allowed to wear?” and “what cultural activities can I perform?” could be expanded. Let’s think about lumberjack shirts and canvas and leather backpacks. Should, I, and the rest of the vintage enthusiasts, think a little harder before we appropriate symbols of labour we have never performed? Given that I will never be a real-life timber cruiser, are there activities that I could undertake that would push this equipment to take on a new, adapted meaning?

As a writer, I understand that there are kinds of truth that don’t line up with ‘what really happened’, or ‘what really happened to me’. As a performer, I tend to love the show more than real life. I don’t think calling clothing a ‘costume’ is an insult. I think the real reason to take on something you do not ‘own’ is to see where it might push your thinking and your doing. I’ve learned from my blisters: certain actions make it harder for you to stop thinking. By engaging the hybrid cultures of Czech tramping and woodcraft in this project, I have to constantly ask the question: what is appropriate to appropriate? I don’t know what the rules are. And, as this project launches, I don’t know how to pack my ‘authentic’ vintage tramping backpack, brought home from the Czech Republic, without 45 minutes of fumbling.

I can imagine how this might change. Certain motions become easier, folds become tighter, rigging more dependable. As cowboy boot blisters become callouses, the trail allows you to forget your feet and think about the fantasy. You can walk down the hill, performing some of the borrowed swagger of the Wild West, and some of the earned swagger of having loaded your pack enough times to do it well. But the rules could change completely tomorrow. I’m looking forward to walking it out with you, my collaborators in Ten Thousand Wolves, and my friends at VANDOCUMENT.

—

Barbara Adler is a writer and musician who has performed locally and internationally as a spoken word artist, accordion player and former member of The Fugitives. Her musical projects are gathered under the banner of Ten Thousand Wolves: an intimately collaborating ensemble whose line-up fluctuates between one performer and ten thousand, but usually settles at somewhere around seven.

Her work on Klasika is part of her graduating project for the MFA in Interdisciplinary Studies at Simon Fraser University. There, she recently committed her first act of musical theater with Pathetic Fallacy, a show about dangerous weather and doomed young love. Her latest project, Klasika, is being created in collaboration with designer Kyla Gardiner, filmmaker/musician Jan Foukal and Ten Thousand Wolves.

—

Brit Bachmann is a Vancouver-based illustrator, installation artist and writer. She has her BFA from UBC Okanagan. When she isn’t secretly filming strangers and/or writing about it, Brit works at VIVO Media Arts Centre. This fall, Brit is exhibiting a drawing series, Climbing Mountains at The Langham in Kaslo, BC.

—

editor’s note

After admiring, for years, the talented powerhouse that is Barbara Adler – writer, spoken word artist, musician,

we’ve proudly had several opportunities to work with her over this past year, from Extravagant Signals

to Accordion Noir

to Pathetic Fallacy

VANDOC has found an artist and friend who is not only fun to watch from the stands,

Adler is someone who brings the game right to you.

Such is the case with Klasika, her newest project.

A complex challenge: experiencing the Czech modern tradition of “tramping,”

– which she dove deep into, cowboy boots and all, through the summer of 2014 –

she has brought it back to her home on Canada’s west coast.

Examining it.

Reshaping it.

Proposing that the concept of our relationship to the wilderness could be approached from an entirely new perspective, and that in this new perspective, entirely new ways of documentation could be attempted.

Fear not the wild, she seemed to be saying to us when she approached VANDOC to work with her on the year-long Klasika.

Scrapes, blisters, a fear of the dark? These places of unknown are where real discoveries and growth happen.

So, naturally, we jumped right in.

—

Klasika photo gallery

Barbara Adler doesn't faze easily. In over a decade of touring, she has told stories, performed poetry, and played her accordion all over North America and Europe.

Pingback: Hey you, it’s me | VANDOCUMENT

Pingback: Call Me Black Wolf: a musical essay | VANDOCUMENT

Pingback: Jen tak cestou z divadla (No. 17) – Divadelní noviny

Pingback: Blisters are the way the leather says ‘I love you’ | VANDOCUMENT

Pingback: High Hair Economics: An Interview with Klasika’s Ashley Aron | VANDOCUMENT