In The Media Tent

Exploring LAND through multimedia art at Digital Carnival 2017

Digital Carnival 2017. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Richmond World Festival might appear, at first, an odd venue for a carefully considered exhibition of new multimedia art. On the sunny Labour Day long weekend, the outdoor track and field of Minoru Park is unrecognisable. Young families mill around happily with big bags of kettlecorn; rowdy teenagers dash between vendors, enjoying the last weekend of summer before school, slowing their step only when the police or security personnel stroll by. Furry mascots wander around, entertaining children. All over Minoru Park – home to the Richmond Art Gallery, public library, and athletic centre – Dragonette can be heard from the main stage, booming a catchy rendition of their hit “Pick Up The Phone.”

In fact, it’s too catchy. I drift toward my destination in a slow and meandering path, doubling back when I get too close, because I want to hear the song from start to finish. Finally, it ends. So I duck into the first of five conjoined tents that house this year’s Your Kontinent Digital Carnival, a series of about 15 multimedia artworks that I’ll take in over the course of the festival. While many of the works are showing on both nights, others will only be featured on either Friday or Saturday.

Digital Carnival, exterior view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Hosted by Cinevolution Media Arts, the Digital Carnival has been a feature of Richmond World Festival since its inception three years ago. Digital art is a good fit for annual public exhibitions like this one: the interfaces invite public interaction, and reveal new uses for technology we might never have considered. Moreover, digital art is dynamic: as technology develops, so too can the works evolve, with artists revisiting their projects in new forms and contexts from year to year.

2017 marks the second year in a row that multimedia artist Wynne Palmer has curated the show. “I think it’s important for artists to show at a venue like this,” she says. “They might love it, they might hate it, but it’s a great opportunity for them to try it out.” Palmer signed on for four consecutive years, with each year’s theme centring on a classical element. Last year’s carnival focussed on water; this year, it’s LAND.

Land is a poignant theme, considering how 2017 is Canada’s 150th anniversary year. Our home and native land. Land is equally geological and geopolitical: when we hear the phrase “a faraway land,” we might think in terms of actual distance, but I’d argue we’re more likely to think of exotic cultures. Still, in a world where migration is a norm – whether from forced displacement or globalised economies – what is “exotic”? What constitutes “foreign”? How does our notion of “land” change? Combined with the ecological crises ravaging the earth, in large part due to overpopulation and the abovementioned economy, issues of land – land use, land ownership, land claims – are further complicated.

However, when I first enter the series of Digital Carnival tents, these questions feel remote. In fact, the people here don’t seem to have a care in the world: the floor is matted with plush beanbag beds, over which kids frolic and grownups lazily recline. It’s a picture of bliss that reminds me instantly of Pipilotti Rist’s 2008 installation at the MoMA in New York, Pour Your Body Out, where the museum’s austere white atrium was filled with cushiony carpeting and furniture, pink velvet curtains, and a large video projection of hedonistic Garden-of-Eden fare. I realise I’ve entered the last tent first, and it’s living up to its name: the Chill Tent.

Chill Tent at Digital Carnival 2017. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Yet, even here, there are works that demand attention. Amid these plush pillows stand two white plinths, each with a set of headphones. With these, visitors can hear the audio tracks of video works projected on four walls of the tent. And some of these works profoundly disrupt the tent’s air of easiness, whether or not they can be heard.

Of particular poignancy is Isabelle Hayeur’s slow video montage Mirages. The camera captures a gradual time lapse of land development – if “development” is really the right word for it. We see fertile agricultural lands slowly marked off, then transformed into an ugly, debris-ridden construction site, and finally into a sprawling neighbourhood of monster houses. Their contrived pomp is cringe-worthy; these knock-off estates look tacky and out of place in North American suburbia. Even though the video is shot near Montréal, the phenomenon is all too familiar in Richmond, with the rich soils of the river delta being paved over for garish mansions that, too often, stand empty.

Isabelle Hayeur, Mirages, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Hayeur leaves us with a note of hope, though: we see weeds and dandelions percolating through construction debris, and a slow return to lush marsh. It’s a nudge that we need to manage the land better, and decide what “home” truly means: a liveable environment, or a vacant house and three-car garage.

When Hayeur’s video ends, Mastic by Sara Gold plays next. It’s the perfect piece for a venue like this: vivid enough to draw the attention of even the most indolent visitors. Its precise blend of beauty and horror draws the tired eye, then jars the mind awake. We see a woman dressed in opulent, rococo splendour – but there’s something crude about her attire, the way her skirt is heaved up with thick garter belts holding her lacy stockings. “Crude” is the operative word here: the woman drops opium pods into a lavish-looking teapot, and pours herself a cup of black oil.

Mastic by Sara Gold, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

The symbolism here is layered: Gold likens our use and extraction of oil to an opioid addiction – deluding, narcotic, pleasant now but disastrous later. Add the extra layer of today’s drug epidemic, and Mastic can be read as an indictment of greed, condemning those who exploit the vulnerable and at-risk for a quick buck. This could be drug dealers hooking their clients on fentanyl, pharmaceutical companies pushing overly powerful painkillers while limiting access to life-saving medication, or oil companies turning a blind eye to environmental crises which, year after year, become impossible to ignore.

Less demanding is Katharine Meng-Yuan Yi’s video Know the Way to What You Are Looking For. This is a two-channel video projected large on adjacent walls, each featuring a hand pointing at a landscape. One is a familiar British Columbia vista. The other, shot from the front of a moving boat, is clearly Chinese; tall karst mountains rise jaggedly from the water.

Left screen: Katharine Meng-Yuan Yi’s video Know the Way to What You Are Looking For, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

The work is pleasant viewing for the lazy beanbag crowd, though it’s inherently self-defeating. This also reminds me of Rist’s work at the MoMA, which many critics hailed as a feminist victory despite its bland, uncomplicated references to original sin – even intercutting footage of a woman devouring an apple with that of a pot-bellied pig, before showing the same woman wading through a polluted swamp.

In Yi’s case, the self-defeat lies in that pointing hand, which is meant to “evoke diverse reactions as it constructs limitless possibilities in narration and interpretation”; she posits that a gesture is more open to interpretation than language. And yet, most communication is nonverbal; pointing in particular usually means one of two things: “Look there” or “go there”. Neither message is out of place in an exhibition that foregrounds movement and migration. But there’s no sense in pretending that the message is ambiguous.

There is no feigned ambiguity in the work screened next to Yi’s, which addresses diaspora much more directly. Ella Cooper’s video work V-Formation features a band of women, all of Black ethnicity, standing in the arrowhead formation of migrating Canada geese (although Cooper’s choice to specify the letter “V” might have other connotations). Their tableaux slowly changes as different women front the “V-formation.” They are never outright confrontational, but neither are they passive. They are welcoming, contemplative, discerning.

Ella Cooper’s V-Formation, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

They stand on a windblown grassland; a forest lies behind them, with mountains rising majestically beyond. It’s a quintessentially Canadian landscape, as though plucked from a Group of Seven painting. Indeed, the scenery invokes a Canada depicted by white men, controlled by white men, written into history by white men. These women of colour brashly reclaim the landscape: for the women that history leaves out, for the First Nations who settled this country long before colonisation, for the diverse people who now call Canada home.

Here, “land” has a double meaning: it is both a noun and a verb. To land is to settle: landed immigrants. Other artists explore this theme: the final video work in the Chill Tent, Acá Nada/Acá Elsewhere, is a short documentary of the aka artist collective of Latin American artists living and working in Vancouver. Consisting of still images, the various photographs fold in and out like the blinds of a rotating billboard. But the work struggles to hold its own at a venue like the Digital Carnival: the images aren’t compelling enough to hold attention. It relies on its soundtrack for contextualisation, and even if a lucky listener manages to get ahold of the single pair of headphones, the video’s narration is hard to follow unless heard from the very start.

Acá Nada/Acá Elsewhere, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

The idea of “landing” is more evocatively conveyed through Milton Lim’s stunning installation in the next tent. The design is all black-and-white: mechanical, informational, sleek. The space is dark, punctuated with silvery white light, as if we’re inside some data-processing machine. Nine phonebooks sit on a desk, arranged like number keys on a telephone; one by one, they are illuminated by nine individual overhead lights. Beyond them, a screen shows the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of random Lower Mainland residences: it’s invasive, even ominous, until we accept the reality that this information is publicly available.

Milton Lim – whitepages, performance. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

For Lim, the phonebook is an archive – a tangible record of diaspora, documenting the influx of Chinese immigrants to BC’s Lower Mainland from the late 1980s through the 2000s. During a performance that accompanies Lim’s installation, the screen does not list names: it lists the word “CHINESE” where a name should be, harkening back to a time when the phonebook excluded immigrants and only listed land-owning citizens. Lim speaks along with, and responds to, pre-recorded audio that muses on this fraught object: a tool for pranksters, a resource for friends, a social map of an ever-changing city.

Like Lim’s whitepages, Facium Terrae by Laura Lee Coles and Rob Scharein is noteworthy for its technical rigour. It is easy at first to dismiss the multipart installation as a family-friendly crowd-pleaser: people are able to look into a camera and have their facial features mapped onto a photograph of lava rocks in Hawaii, projected on a large wall. It’s a popular, interactive piece that draws waves of Friday night festivalgoers. But more interesting than this are the monitors off to the side.

Laura Lee Coles & Rob Scharein – Earth Face. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

The screens display blurry slideshows, ostensibly of more rocks. At first, they strike me as unremarkable. But as I pass by, a volunteer hands me a pair of stereoscopic glasses and invites me to stand on a mat in front of one of the screens. The images become clear: and as I view the photographs in anaglyphic 3D, features begin to emerge from the lava beds. In every rock there are faces, gargoyle-like and grotesque, staring back at me. It evokes a sense of animism: an idea that the earth is watching us. Although I’m wary of anthropomorphising the land, these ghoulish faces remind me that stones – so easily dismissed as lifeless – are in fact vibrant, transformative traces of the planet’s energy at work.

On Saturday night, this tent is home to a different installation: Shadow Forest by Vancouver-based duo Mind of a Snail Puppet Co. Acclaimed for their visually rich storytelling through theatre and puppetry, Mind of a Snail has created a series of landscapes inspired by Emily Carr paintings. Overhead projectors have been set up on stacks of collapsible tables, lending Shadow Forest that DIY feel characteristic of Mind of Snail’s work.

Mind of a Snail – Deep Forest Paintings Emily Carr. Photo by Ash Tanasiychuk

Guests move paper puppets, scraps of found material, and bug-shaped toys across the slides, animating the forest scenes projected onto the tent walls. Some visitors eschew the props altogether, engaging in shadow puppetry with their hands. It’s nice to see even the adults let loose and act like kids; many are engrossed in bringing the installation to life. Shadow Forest is less scientific than Facium Terrae, but both installations are family-friendly favourites with an environmental ethos.

Mind of a Snail – Deep Forest Paintings Emily Carr. Photo by Ash Tanasiychuk

This ethos persists forcefully through the next tent, The Voice of the River. This is an ongoing project by artists Marina Szijarto and Glen Andersen, who have invited the public to shoot 15-second films with the Fraser River as the subject; their aim is renew a respect and appreciation for the Fraser River, whose fragile estuarine ecosystems are right here in Richmond. They compile these short clips into long montages, and will later present them on World Rivers Day.

Glen Andersen & Marina Szijarto – Songs of the River. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

For now, the films are screened on sheets draped across from one another; they’re flanked by white curtains that resemble the white crests of waves. Silvery fish silhouettes are hung throughout the space. This tent feels cooler and airier than the others; soft blue light tints the walls, and for the first time I notice the turf flooring. Anderson mentions that the tent was meant to feel like a sanctuary, which it does. It feels sad, too, with those ghostly silhouettes: it’s a celebration of life in the truest sense, honouring the Fraser River’s vitality while also lamenting the many threats that daunt it.

Between the two video projections is an offering of sorts – the implements of a little ritual. A small dais sits aglow with tea lights, with a bowl of water set atop it. It’s a gentle reminder that for much of human history, rivers have been revered as protectors, life-givers, and deities. Perhaps it’s time to restore some of this respect.

Glen Andersen & Marina Szijarto – Songs of the River. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

The last tent – or the first, if you go in order – is also devoted to giving thanks. Here, performance artists Minah Lee and Marcelo da Silva use the language of preserves – salts, spices, canning – to record the audience’s messages of love for the earth, which will be buried in a jar like a time capsule. Every person who professes his or her love receives kimchi handmade by Lee.

Minah Lee & Marcelo da Silva – How to Ferment Love Letters. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

The installation has a festive atmosphere, with a stage swarmed by thronging people, who Lee addresses enthusiastically through a megaphone. It’s brightly coloured, too, with video mapping jars onto stacked boxes and projections on the ceiling – except, in lieu of Korean kimchi, these jars contain historical illustrations of the Brazilian slave trade, a nod to da Silva’s ancestry. In another wordplay around earth and burial, these globetrotting artists seem to be preserving their own roots.

On Saturday night, Play Workshop takes the stage in this tent. It’s a family-friendly, interactive workshop hosted by Alanna Ho and Nathan Marsh. At a glance, the workshop looks lighthearted, colourful, and frankly a bit frivolous. But the pair of educators have in fact devised an ambitious soundscape, challenging their visitors to listen closely, ask questions, and engage. Play Workshop is in fact an extension of Ho’s Rainbow Forecast Project, an initiative geared at introducing concepts in sound design and media art during early childhood education. I think Ho is onto something here: listening is too often reduced to a command, a form of control, within pedagogy. Listen to the teacher. Given the chance, children could open their ears – and minds – to so much more.

Alanna Ho & Nathan Marsh – Workshop. Ash Tanasiychuk photo

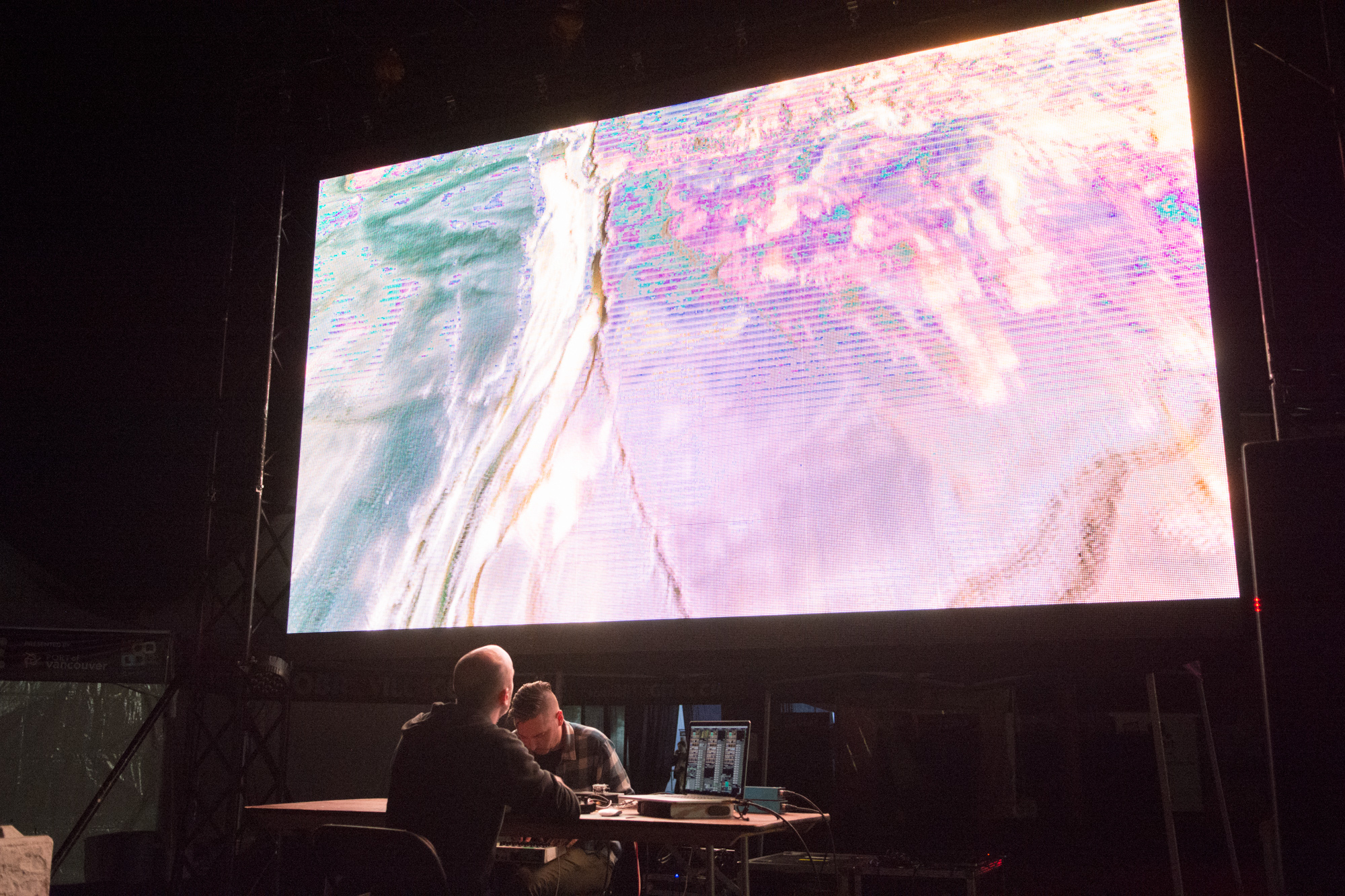

Outside of the tents, the exhibition continues. On a stage, Constantine Katsiris and Ian Ross present Eye of the Storm, a feat of live image and sound mixing in which the artists blend raw data and shortwave radio frequencies in an improvised performance. The use of radio frequencies is clever; it’s another invisible force of the earth, pulled seamlessly into digital art. The work is synergetic and synaesthetic, as Katsiris and Ross respond to one another in the moment.

What results is mesmerising: a churning, greyscale image that at times resembles stormy, swirling clouds, which then coalesce into dense, planetary spheres, their orbs broken up by sudden, random distortions. It reminds me of how we as humans like to see the earth and its ecosystems as neatly organised and perfectly balanced, when in fact, ecological research have shown us how chaotic and eternally in flux these systems are if viewed on the massive scale of geologic time.

Constantine Katsiris & Ian Ross – Eye of the Storm. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

All throughout the piece, the screen is flecked with little disruptions – scuffs and spots of dirt or dust – as though this purely digital artwork were running through an old-fashioned film projector. It tinges Eye of the Storm with an avant-garde, cinematic flair; it’s like watching found footage of something surreal, captured by accident.

Eye of the Storm takes place only on Friday night. On Saturday, the screen glows with Sonny Assu’s distinct brand of art: eye-catching First Nations motifs, infused with references to pop culture. Assu’s works discuss serious concerns with a dry, tongue-in-cheek humour, demanding that we never take for granted the fact that we live on stolen lands, speaking an imposed language and practicing settler cultures.

Sonny Assu, 1UP, video installation. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Contextually, his work is a perfect fit for this exhibition. The trouble is, it takes this perfect fit for granted. There is very little information about the piece – only the title 1UP – which is a problem at a venue like Richmond World Festival. LAND is an opportunity to reach hundreds of interested, open-minded people who might never have encountered Assu; so I wish he made it a bit easier for them to take away his message, no matter how obvious it might seem. Instead, the work feels like it’s sitting on its hands here, offering little more than a cool background for selfie-snappers. Definitely not the point.

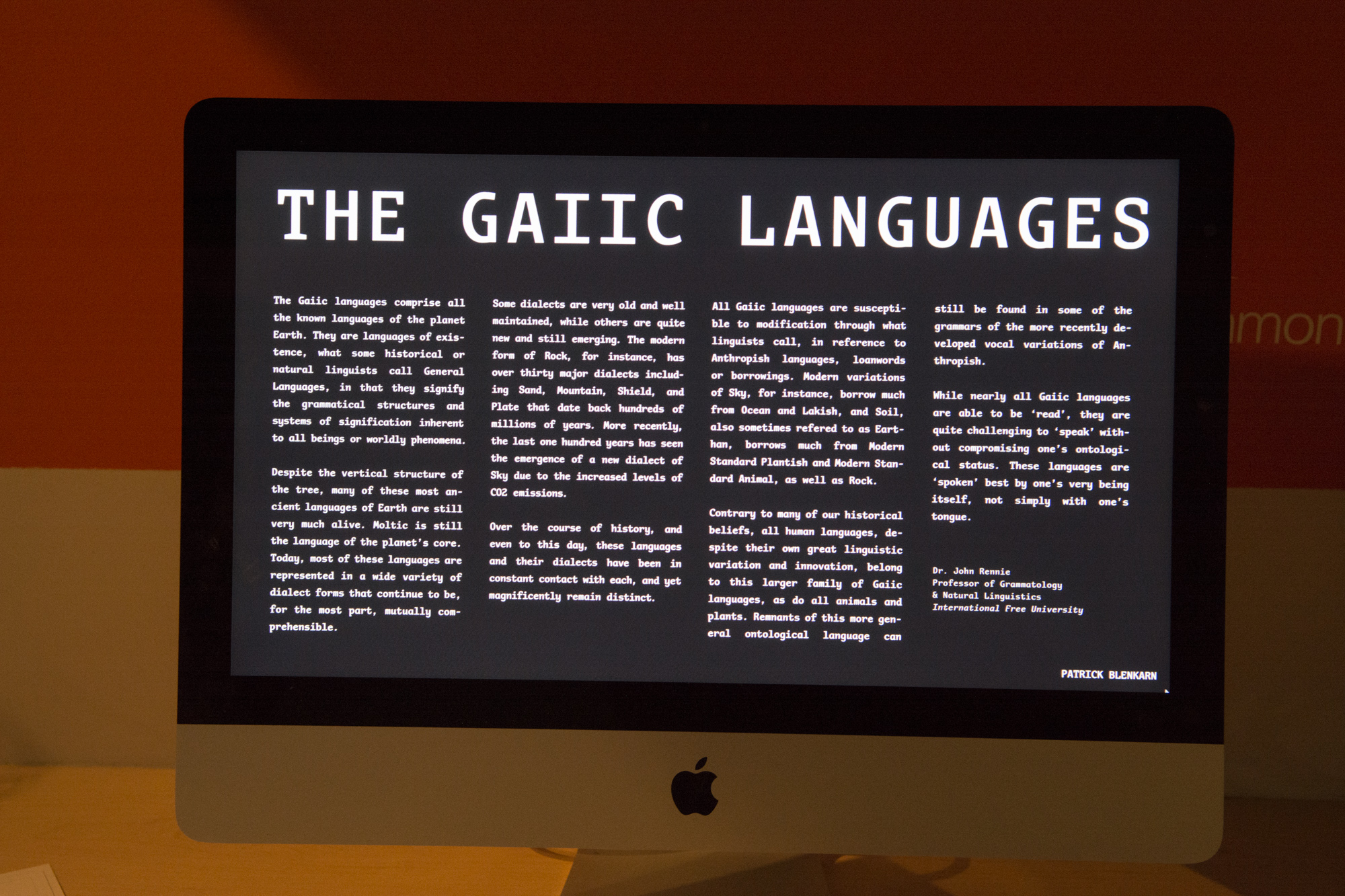

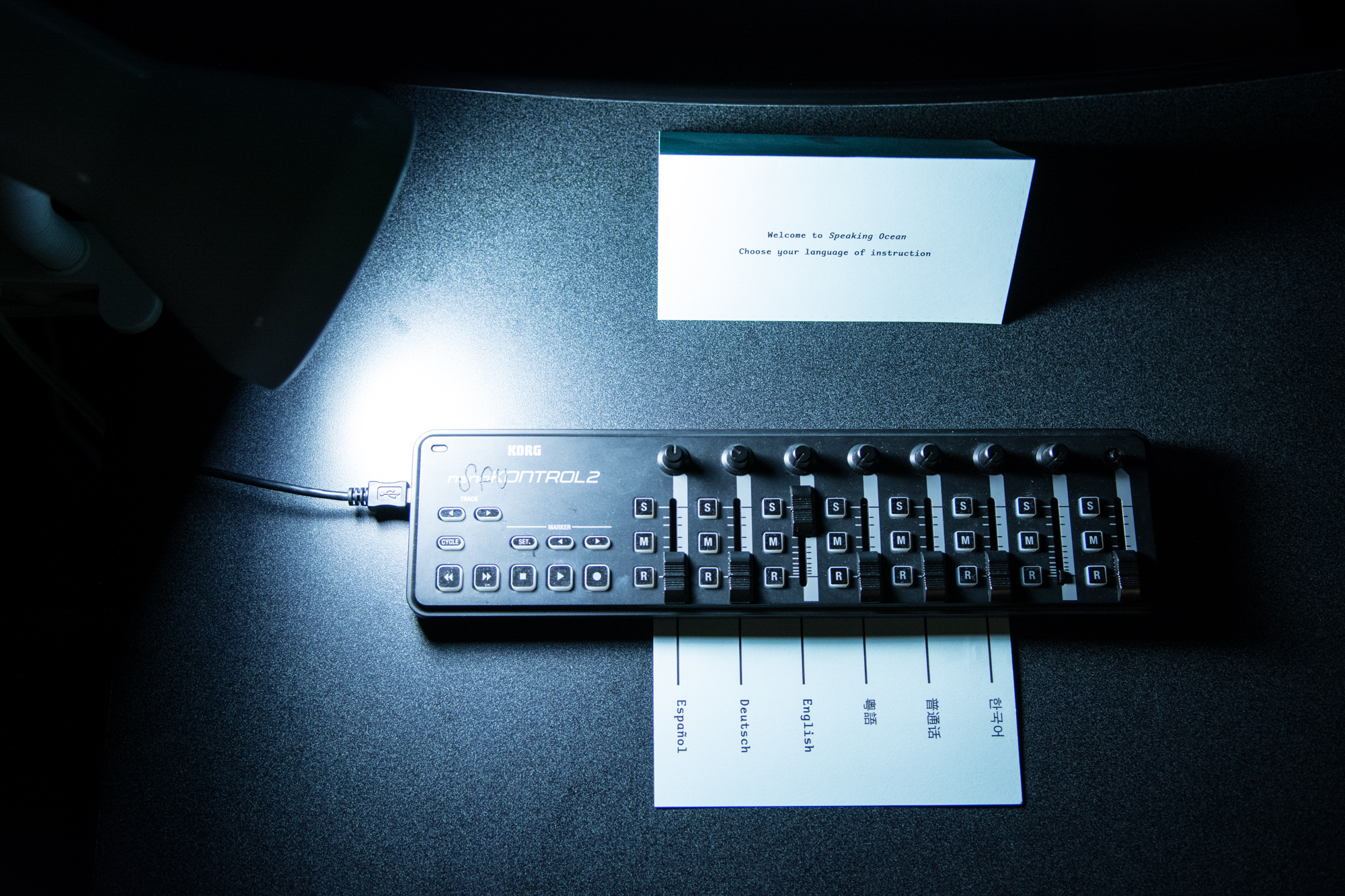

Further beyond this, away from the main tents that comprise the Your Kontinent Digital Carnival, is Patrick Blenkarn’s interactive piece Speaking Ocean: Basic Expressions. Based in the Media Lab next to the Richmond Art Gallery, Blenkarn’s work presents a lesson on how to communicate in hypothetical, primordial languages spoken among all earthly phenomena. The “Gaiic” languages (a play on the term Gaia) encompass all languages on Earth. Each is distinct, but many are mutually intelligible.

Patrick Blenkarn, Speaking Ocean, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Blenkarn’s installation has a humourous ring to it: it parodies our obsession with words, even our fetishising of foreign languages and accents. His work is technically brilliant, too: one can choose to hear the full lesson on “speaking ocean” in English, German, Spanish, Cantonese, and Mandarin.

Patrick Blenkarn, Speaking Ocean, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Trying to communicate with the environment, and the other creatures with which we share our planet, is a nice idea. But the fact remains that languages – words, grammars, alphabets – are reductive, abstract, and sequential. They’re antithetical to the concrete, simultaneous, non-rational state of nature. I’d go so far as to say that linear, logical consequences of language – and how it has organised human thought and action for the last 5,000 years – have a lot to do with why humankind and nature are so often posited as two separate, often opposing forces. The very notion of “speaking ocean” is rife with problems. And Blenkarn seems to be aware of this: every phrase spoken in “oceanic” sounds like little more than a crash of white noise.

It’s the very failure of language that drives Cindy Mochizuki’s breathtaking performance, Compass, in the theatre next to Blenkarn’s media lab. Compass derives from Mochizuki piecing together her grandmother’s stories of displacement and dispossession during World War II. The complexity lies in the fact that her grandmother seldom spoke of these years; originally titled A Compass For Your Silence, Mochizuki’s work delves into the subjective, the experiential, the speculative. She does not aim to document the years of Japanese-Canadian internment, but rather to chase their lingering spectre.

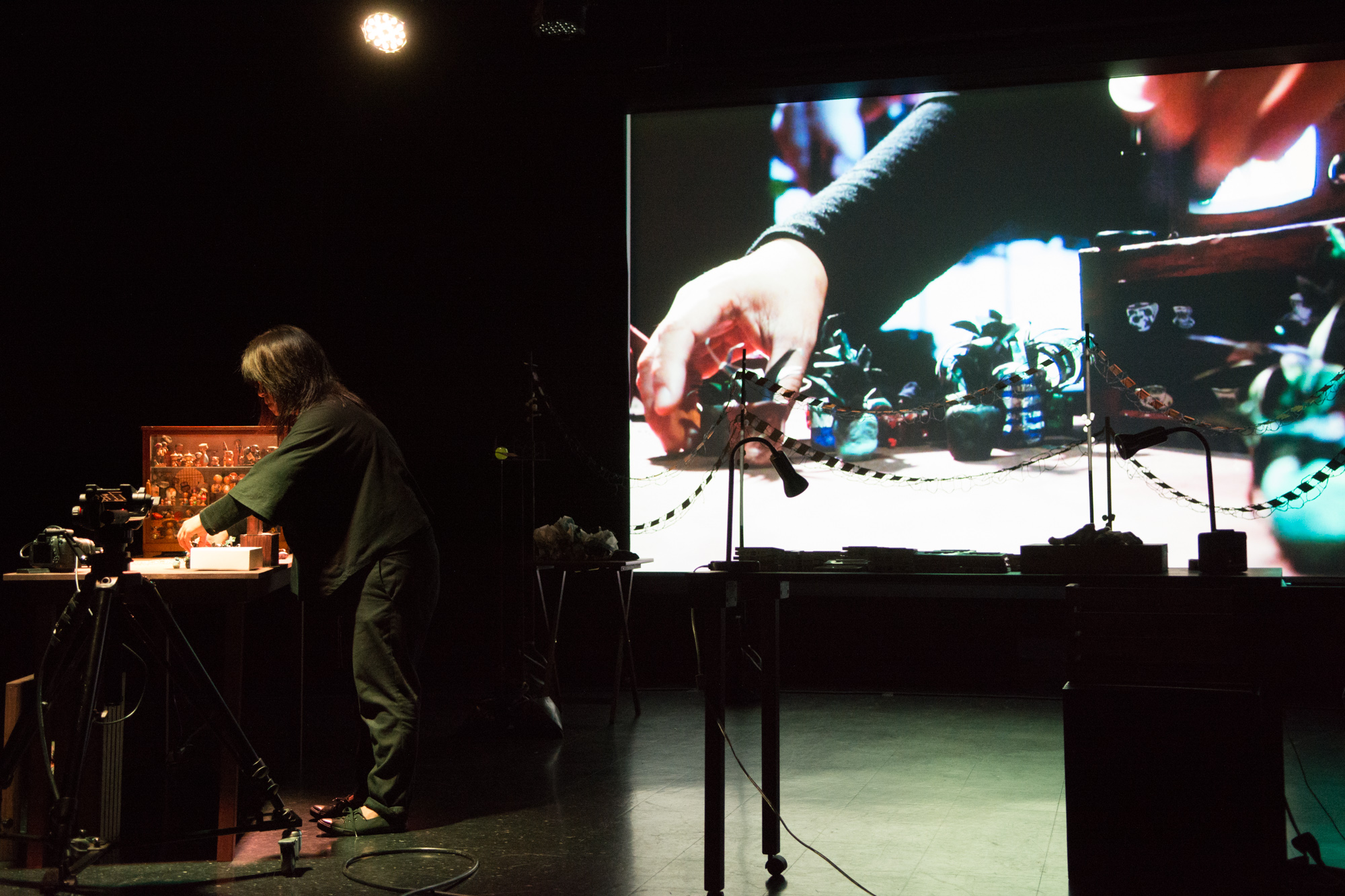

Cindy Mochizuki, Compass, performance at Digital Carnival 2017. Ash Tanasiychuk photo

Compass is nevertheless thoroughly researched. Mochizuki leafs through her grandmother’s documents from when she owned and tilled a strawberry farm out in Walnut Grove; she plays Roosevelt’s address following the attack on Pearl Harbour from a small cassette. But most affecting are the figurines that people Mochizuki’s memorial world: paper dolls, hand puppets, and her grandmother’s collection of wooden kokeshi from Japan, which stand onstage in a glass cabinet.

Mochizuki’s props and puppets are laid across two desks. Behind her is a large screen, which shows a live video feed from the cameras that she moves around her set, interspersed with the artist’s hand-drawn animations. Throughout the work, Mochizuki glides gracefully between the desks, arranging her props with careful precision. In one memorable sequence, she recreates a vision of her grandmother’s berry farm, complete with strawberry bushes picked over by tiny, handmade dolls, her camera roving among the miniature rows of workers.

Cindy Mochizuki, Compass, performance at Digital Carnival 2017. Ash Tanasiychuk photo

Mochizuki clearly defines the sense of loss: she weaves an intricate vision of life before 1942, allowing the shadow of persecution to hang over the audience. Compass is especially forceful in Richmond, which had a significant Japanese-Canadian community prior to World War II. Once internment was ordered, the fishing village of Steveston became a ghost town; the Japanese-Canadian inhabitants were forced to abandon their homes, which were promptly looted. It’s a sad, shameful chapter of our history, but one that deserves foregrounding at Richmond World Festival. Kudos to curator Wynne Palmer, as well as artistic director Lynn Chen Groppi and project director Yun-Jou Chang, for spotlighting Mochizuki’s brilliant work.

Altogether, this year’s carnival comes together splendidly. There are only a couple misses among the many hits, and it is a rare chance to bring swarms of people through contemporary art installations that would otherwise reach only specific audiences – those at media arts festivals, or galleries and artist-run centres. For me, the standouts are Mochizuki and Hayeur; their works are aesthetically captivating, deeply researched, and pertain to broad issues while resonating specially in Richmond. I look forward to what Palmer has in store for the next two instalments: “air” and “fire”.

For now, she sticks the landing.

Curator Wynne Palmer and writer Justin Ramsey at Digital Carnival

review written by Justin Ramsey

photos by Ash Tanasiychuk

Digital Carnival artists. Photo by Ash Tanasiychuk

-

- Left screen: Katharine Meng-Yuan Yi’s video Know the Way to What You Are Looking For, installation view. Ash Tanasiychuk photo.

Justin Ramsey holds a Masters in Comparative Media Arts from Simon Fraser University. He works as an arts administrator with various institutions including Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, and Republic Gallery, Vancouver. As a freelance writer, Justin has contributed to several publications and platforms, including MONTECRISTO Magazine and NUVO Magazine.