The Lesson – Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools

Exhibition at Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery continuing a process of healing and education through art

Words by Shalon W-H

Images provided by Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery

A witness is defined as one who sees or experiences an event or occurrence take place; one who makes testimony, who testifies, who attests the truth of. To be a witness is to state one’s belief in; give evidence, give proof.

I entered the packed and bustling Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery located at UBC’s Point Grey Campus on the traditional, ancestral, unceded territory of the Musqueam people right on time for the 1pm performance. Hip hop played while people milled around the gallery noisily, chatting, mingling, and looking at the various pieces hanging from walls and installations occupying the first floor of the gallery. The energy in the room was alive but serious; the air felt hot and muggy between the bodies, but the tall white walls, grey concrete floor, and the underlying thematic nature of the opening created a certain coolness in the space.

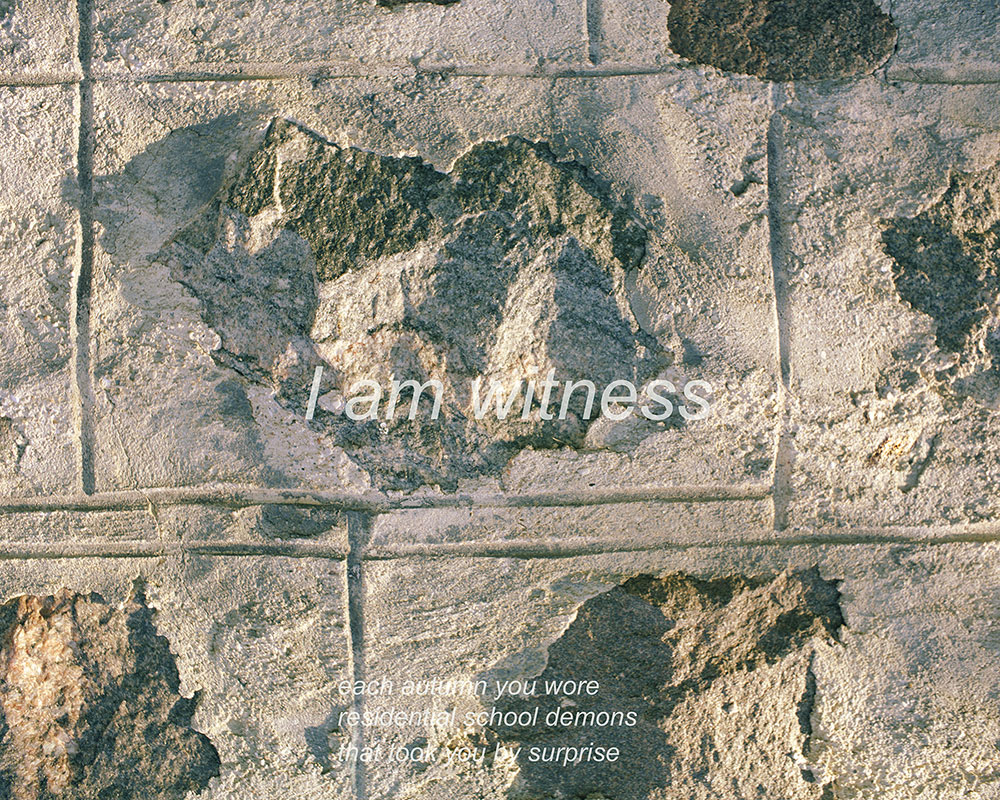

Sandra Semchuk and James Nicholas’ Camperville Residential School, Manitoba, 2006-10, lightjet prints

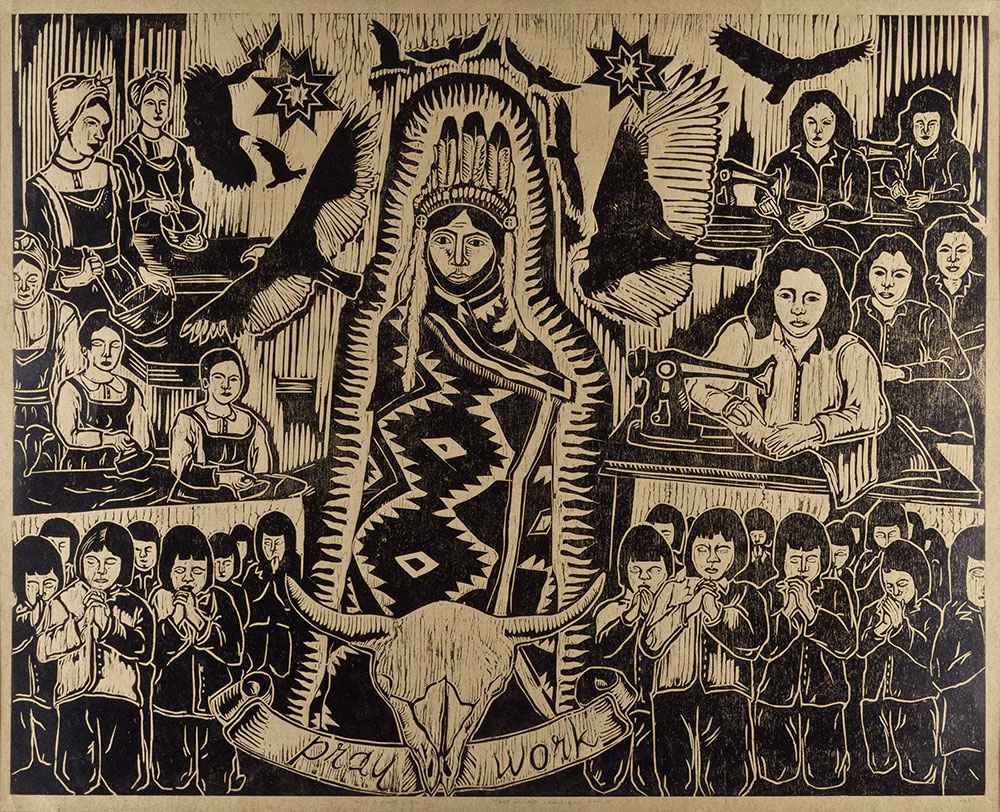

Things were running slightly behind schedule, but slowly everyone gathered into a side room with a life-sized classroom installation in one corner; the space where The Lesson, a performance installation by Joane Cardinal Schubert, would shortly begin. Viewers piled into the room; quickly filling the audience seats, then sitting on the floor and then filling the remaining standing room to watch the performance begin – allowing everyone in the room to “witness” what would have resembled reality for many residential school students.

The Lesson features ten black desks and chairs, each with one or two neatly stacked white books on them with titles like Ethics and Rules. The walls are large black chalkboards covered with words, names, memories, and lessons from the past. A metal stool with a dunce cap placed on top of it sits alone in the back of the room. The chairs are bound together with rope signifying the restrictive binds that continue to tie residential school survivors to one another and to history.

Each desk is topped with a single red apple with a hook screwed into it. “Apple” is a term used by First Nations in a derogatory way toward other First Nations; it implies that one is “Red on the outside, but white on the inside.” The screws represent the ways in with First Nations have continually suffered from systems of racism, oppression, violence, and injustice.

The short performance began when nine First Nation students piled into the classroom single file, relentlessly blowing high pitched whistles and pointing to the chalk boards. The intense screeching sound of the whistles was unbearable – most people in the audience had to cover their ears for protection against the piercing scream. The teacher stood at the front of class loudly ringing a hand-bell. Every student wore tags that read “thought police.” As I witnessed this performance, all my senses were instantly engaged – this was a visceral experience, and the audience was meant to feel discomfort. The class was seated and the whistle blowing came to a halt – a very clear statement on the whistle-blowing that needs to continue, to expose years of residential school violence, abuse, and misconduct. After this, the students chant the lesson that is written on the chalk board in unison: “In the beginning…”

This installation originated in 1989 and was first exhibited in Montreal at Articule Gallery. It later evolved into a full performance piece when ten Aboriginal People were invited to participate as the students, giving a live voice to the text on the blackboard of truth, and to the many people who had stories to tell. Additionally, the ten people who change with each showing, are given time during the performance to add their own personal shared experiences and stories.

The class is dismissed and files out of the room to complete the performance. The installation is interactive: audience members can add their own experiences, thoughts, or memories to the blackboard with chalk that is left out for everyone.

Following the performance, short speeches were given to introduce the exhibit. Musqueam elder Larry Grant delivered the welcome speech for Witnesses and thanked the many individuals who helped to make it a reality. He acknowledged everyone’s presence on unceded traditional territory and explained how his own partner attended Port Alberni Residential school, and had chosen not to attend the opening gallery event because it would be too painful of an experience. Grant acknowledged the strength of spirit and courage needed for each artist to share their work and story openly. The artists featured in Witnesses have bravely chosen to show, through art, their memories of experiences that they have been deeply affected by. Through this sharing of stories, this exhibit continues the process of healing that has been occurring over the years. It also opens up these stories to a public who might be unaware of the colonial history often unacknowledged or conveniently forgotten in this “peaceful” nation we call Canada.

Chief Robert Joseph, hereditary chief of the Gwa wa enuk First Nation, spoke next and talked about the role of art in raising a Canadian historical awareness and social consciousness around the Canadian Residential School history. Joseph’s words were full of hope when he said that Canadian people need to listen to their hearts and become aware of their histories. He believes darkness can turn to light and that the real power of the Witnesses exhibit lies in its ability to start discussions about the legacy of Canadian Residential Schools, and through finding what he calls a “real Canadian consciousness.” Joseph stated, “The promise is in the present moment, when we begin to think about our history and moving forward in a new way.” Witnesses provokes movement towards this new future through and towards a continuously needed dialogue around understanding, embracing, and honouring any person who experienced or has been effected by this dishonourable fact of Canadian history.

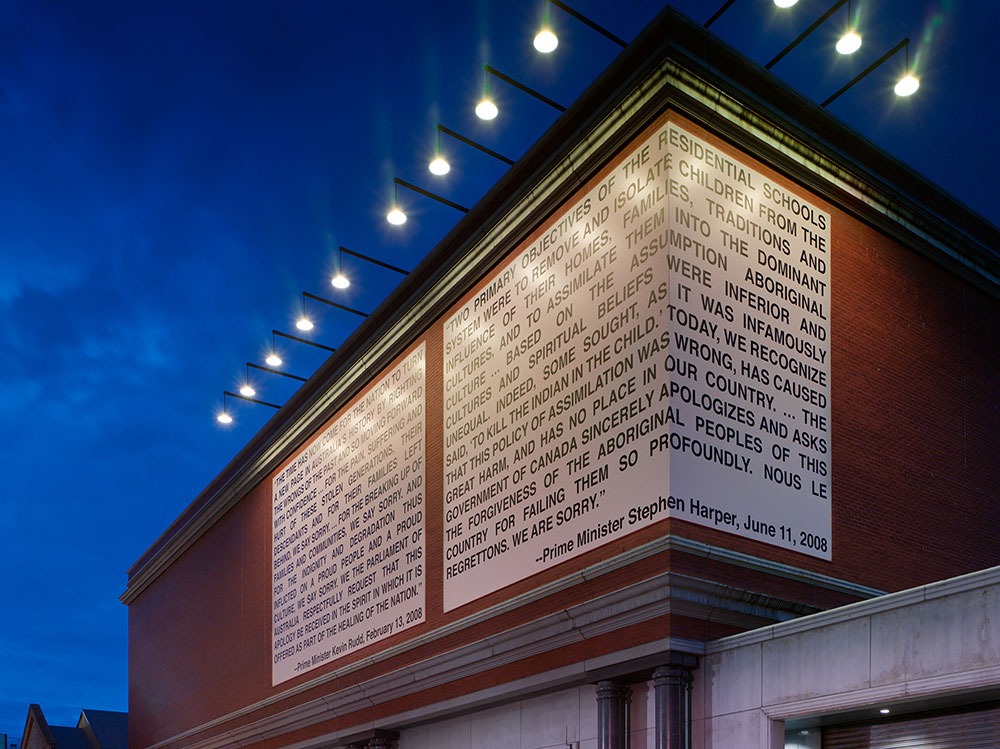

On June 11th, 2008, The Canadian Government issued an “official” apology, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established to review and hear experiences of former residential school students. Vancouver is home to this year’s National Reconciliation Week (September 16th to 22nd 2013 held at the Pacific National Exhibition). People are encouraged to come and share their truth about the schools and their legacy, to witness and celebrate the resilience of First Nations cultures.

Cathy Busby’s WE ARE SORRY, 2009, Installation view, Laneway Commissions, Melbourne. Photo: Peter Bennetts

—

For more information:

Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools

September 6-December 1, 2013 @ Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery

belkin.ubc.ca/current/witnesses

J’ai lu The Lesson – Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools | VANDOCUMENT avec beaucoup d’intérêt et ont trouvé divertissement d’ailleurs facile à lire contenu. Ne manquez pas de prendre soin ce site est très bon .