National Stolen Treasures

Dylan Robinson discusses art music's indigenous inclusions

Written by Dillon Ramsey

Photography by Ash Tanasiychuk

Go into any of Canada’s “great” museums and you will more than likely come face to face with collections of First Nations artefacts acquired by means that could be called questionable at best. Indeed, colonial Canada has long made a point of stockpiling the ceremonials of its indigenous peoples, cultivating something of a faux national identity predicated on stolen and imitated culture. But of course, it is often only through physical objects, such as clothing and masks, totems and utensils, that this culture is conveyed; it’s not as easy to put music in a museum, as sounds and words cannot be confiscated so easily from their original owners and put in an exhibit, or a storage unit, somewhere. Or can they? Actually, archives all across the country are “home” to hundreds of traditional First Nations songs which were recorded, catalogued, and eventually appropriated by ethnographers, composers, and ethnomusicologists throughout the twentieth century. There is now a handful of contemporary scholars committed to finding out what has happened to these works, and to what extents they have been exploited, transformed, or reclaimed.

One such scholar is UBC’s Dylan Robinson, a postdoctoral fellow in the First Nations Studies programme whose ongoing work involves critically interrogating the ways in which indigenous songs have been appropriated by composers throughout Canadian history. He recently co-edited a collection of works called Opera Indigene: Re/Presenting First Nations and Indigenous Cultures, and he is currently completing a new monograph, Songs Taken for Wonders: The Political Aesthetics of Indigenous Art Music in North America. And tonight, Robinson has been invited by SFU’s Vancity Office of Community Engagement to present a public lecture concerning his inquiries into indigenous inclusions in Canadian art music, and the multiple projects and productions which have informed his research.

It’s a cool, grey autumn evening, and a group of about thirty have gathered in the Djavad Mowafaghian World Art Centre, glowing dimly but warmly, to hear Robinson speak. Following a formal introduction from programme coordinator Andrea Creamer, Robinson takes the podium with a politely affable and academic charm. Being a member of the Stó:lō Nation, Robinson begins his presentation in his people’s traditional language, modestly confessing that he is still in the process of learning it, and commences his lecture.

Robinson’s investigation into the adaptations and appropriations of First Nations culture started when he was a student contemplating opera, and thinking about the interesting integrations and collaborations that have merged the medium of classical music with indigenous songs, dances, and customs. To demonstrate how these cultural convergences can be enriching and cooperative experiences, Robinson comes ready with a dozen compelling examples. The violin and cello virtuoso Dawn Avery, and her musical allusions to her Mohawk ancestry; creative collaboration between Laura Ortman and Raven Chacon; the now-famous Four Seasons Mosaic; and Tanya Tagaq‘s work with the Kronos Quartet. “You couldn’t begin to imagine how many concertos for throat singers there are,” chuckles Robinson lightheartedly. He explains that these types of cross-cultural art music ensembles only emerged over the last ten to twenty years. Of course, cross-cultural art music has a history in Canada that dates to the 1920s, but in most cases these endeavours were neither collaborative nor entirely ethical.

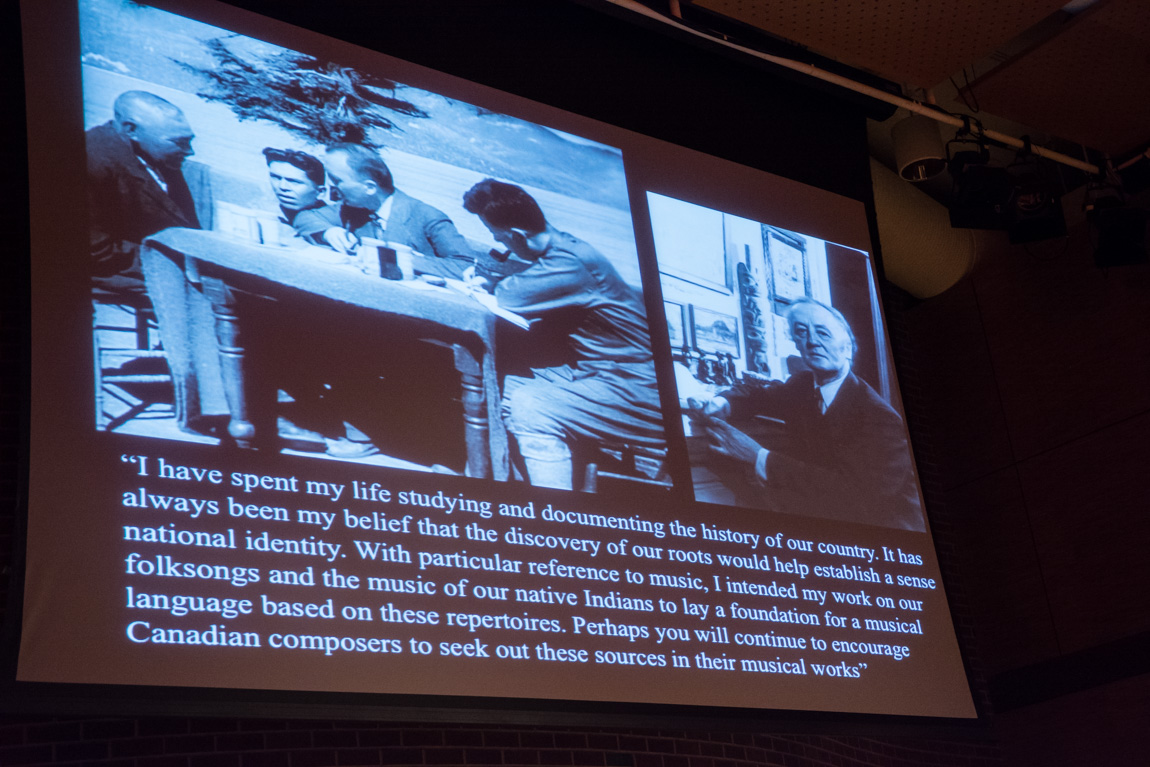

Robinson talks animatedly about the culturally tactless approach taken by some of Canada’s canonical musicians and ethnomusicologists, such as Marius Barbeau and Sir Ernest MacMillan in their recording and appropriation of First Nations traditions.

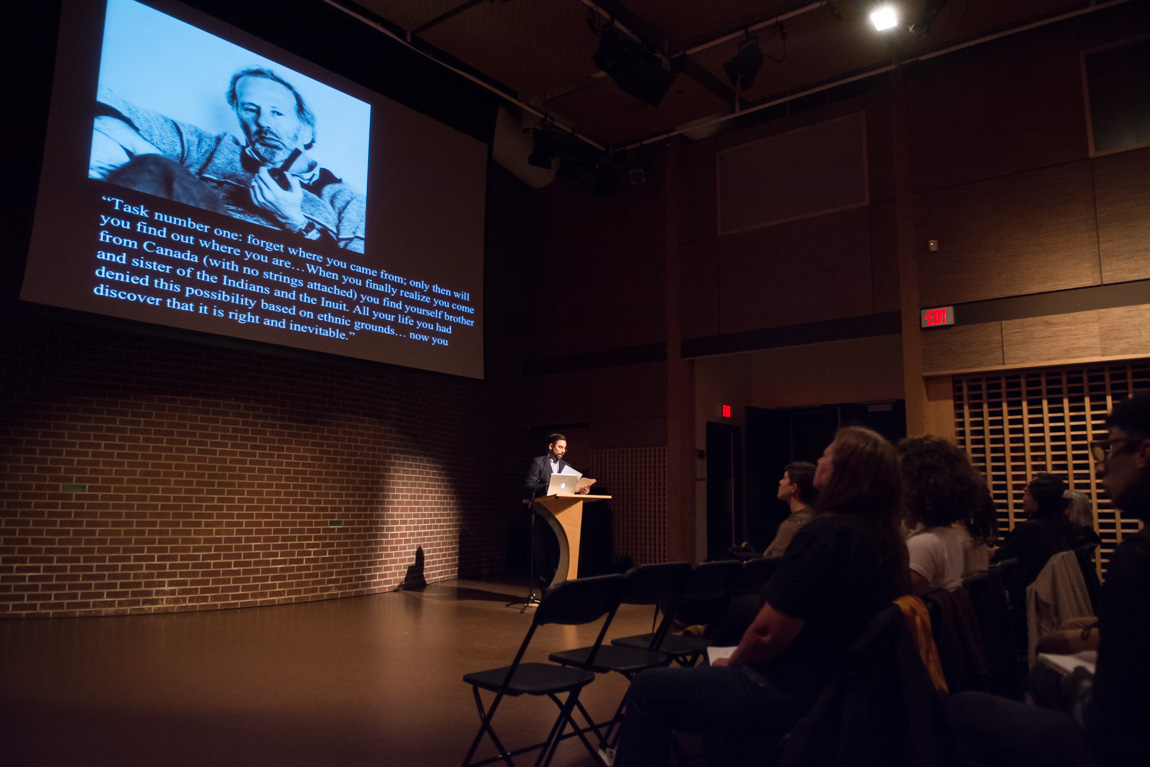

His critique also extends to more recent, even enlightened, music scholars such as Ida Halpern and R. Murray Schafer. Common to all of their researching, collecting, archiving, and reinterpreting of First Nations songs is a somewhat self-congratulatory rhetoric of inclusion; they hope to synthesise an authentic “Canadian sound” by integrating the cultures of Canada’s indigenous inhabitants. Canadian composers throughout history have waxed sentimental about “a unique Canadian musical identity”, “inheriting traditions”, and “[forgetting] where you came from… [and to] finally realise that you are brother and sister of the Indian and the Inuit”.

Robinson refers to an article from The Province newspaper whose tagline reads “Native Songs Saved”; and as the reporter states, “What could be more Canadian?” All the while, proper protocols are constantly being sidestepped. People don’t realise how easily they comply with the continued colonialist project, even as they endeavour to be considerate and benevolent. Several instances of well-meaning but conspicuous cultural ignorance come to my mind. Just think about Emily Carr, a Canadian legend whose arguably admirable attempts to depict the disappearance of First Nations people and communities, in the end served to exoticise or pastoralise her subjects, entering them as a chapter, or a footnote, in the grand narrative of Canadian settlement. More recent is the instance of the inuksuk, an age-old icon of the arctic anachronistically adopted to somehow symbolise the spirit of the Vancouver 2010 Olympics.

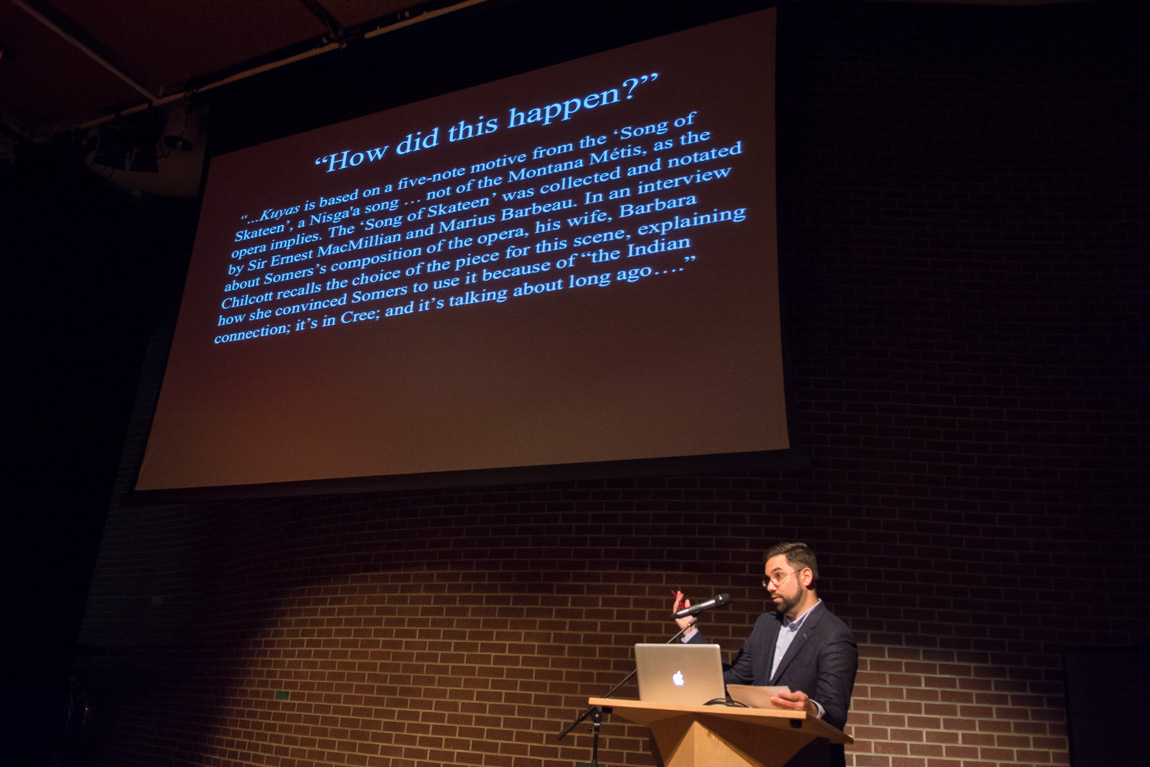

So it is with music. Robinson rightly points out that the Western notion of art music as a medium of aesthetic contemplation doesn’t translate accurately to a First Nations model, wherein music serves fundamental functions in daily reality. “Everything from family history to purposes of law, to healing, to markers of social status” says Robinson of music’s role in indigenous society. “Songs are more than just as aesthetic form. They are functional, and do things in the world.” He cites a court case in which a land claim was settled in favour of a First Nations band because a judge permitted a song to be used as proof that the disputed territory traditionally belonged to the people. So it’s easy to imagine how problematic it is when indigenous songs are included in art music disingenuously deprived of their social and historical contexts. Such is the case in the famous Canadian opera Louis Riel, composed by Harry Somers for the country’s centennial celebrations in 1967, in which one of the arias is passed off as an original song of the Montana Métis. In actual fact, it is a five-note motif copied straight from the “Song of Skateen”, of British Columbia’s Nisga’a people.

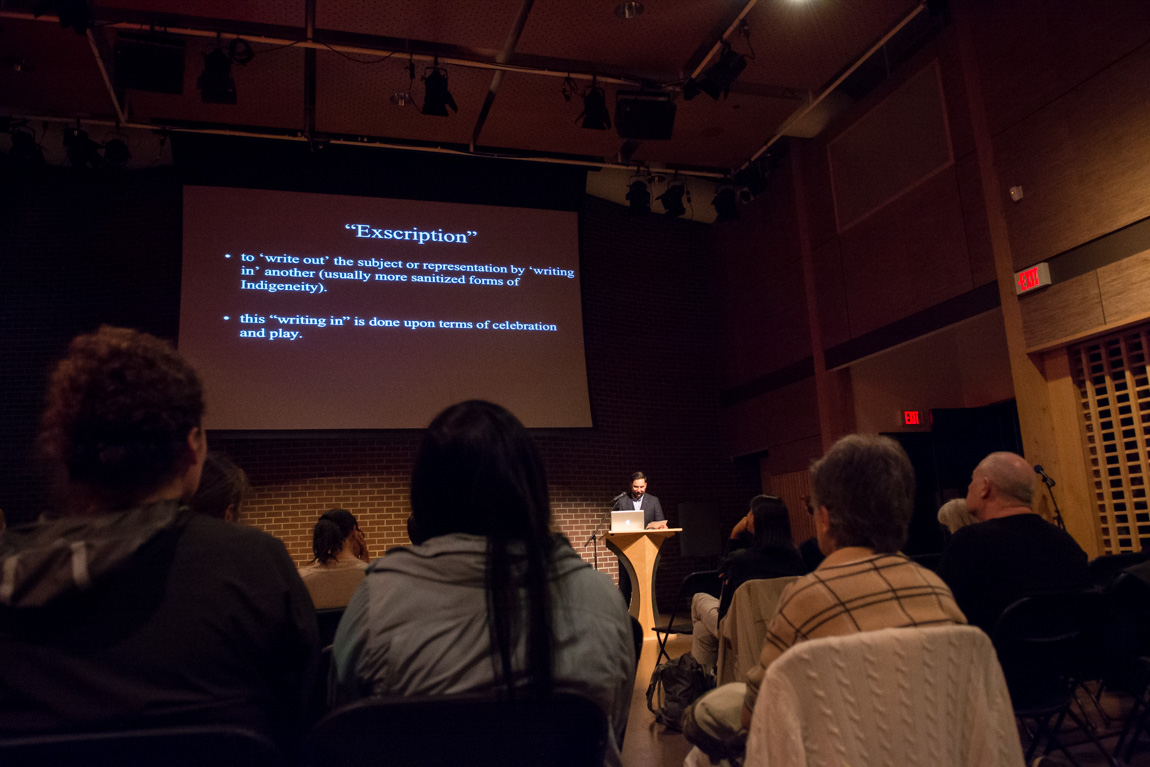

Robinson prefers the term “exscription” to refer to these inclusions of indigenous culture in Canadian art music. Exscription essentially means “to write out one subject by writing another in”, and is employed in the revisionist history of the First Nations’ struggle in Canada, pitching a prettier picture wherein everyone gets along and cross-cultural collaborations turn out genuinely “Canadian” pastiches that derive hybridised inspirations from friendly indigenous and settler societies. A perfect example of exscription would be the “sanitised indigeneity” of the Stanley Park totem poles, where the presence of officially-sanctioned monuments obscures the forced extirpation of the original First Nations peoples from the parklands. It is a way of wilfully ignoring important social issues, and celebrating cross-cultural or “intercultural” collaborations that are still couched in Western formalities. Such inclusions are often thought of as being “past critique” by the lay person. But as Robinson astutely points out, such ideas subscribe to “a settler structural logic, without unsettling the norm”.

As emphasised both in the beginning and end of Robinson’s speech, there are still several instances of positive, productive, and progressive intercultural projects in which First Nations traditions are included in art music; he returns to the example of Dawn Avery and R. Carlos Nakai‘s Lake That Speaks. What’s really important is to be aware of the complex issues that inhere in cultural appropriations, and to share our knowledge with others in our communities. And it’s also important to claim ignorance, Robinson reminds us. “It’s okay to say ‘I don’t know; but I’d love to know'”.

—

SFU’s event page with details: sfu.ca/sfuwoodwards/events/