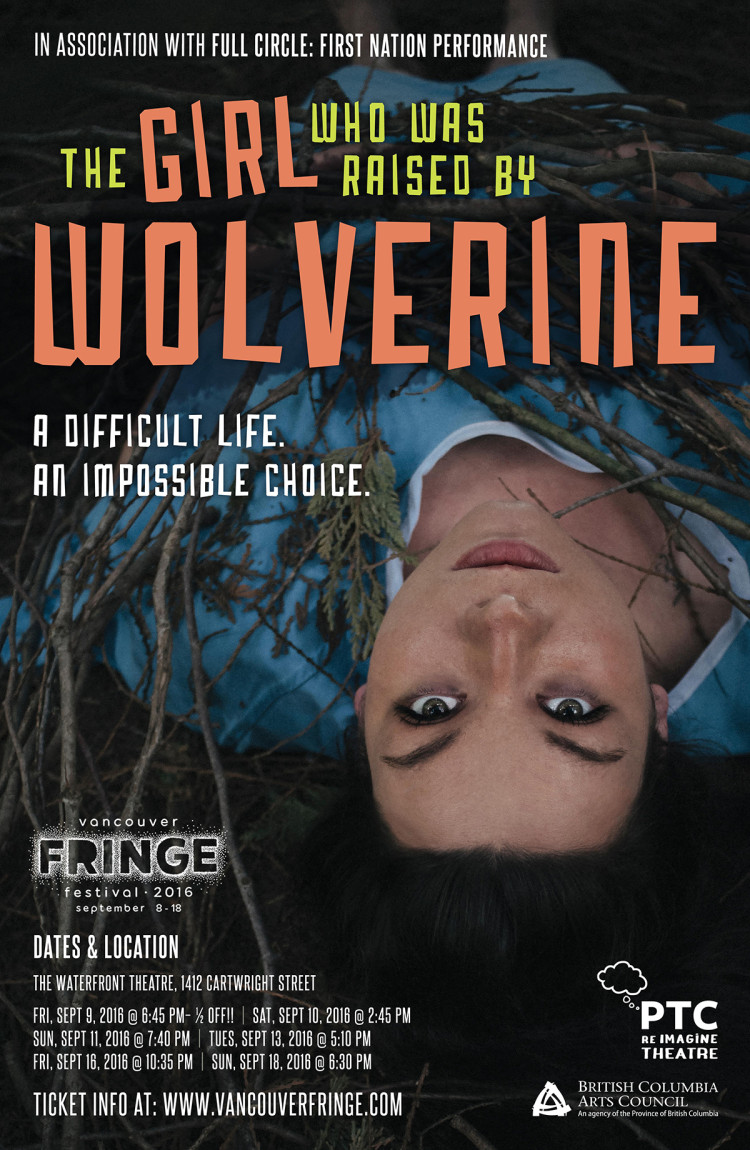

This Isn’t Fan Fiction

The Girl Who Was Raised By Wolverine, reviewed

Upon entering the Waterfront Theatre, I’m greeted by a shorthaired woman with a pretty, welcoming smile, and a man who sits cross-legged and barefoot behind her, in a somewhat meditative posture, next to a large white bucket. Both people are dressed normally, except for what appears to be an item of shaggy grey fur on both their costumes. As I walk by, the woman gives me a round, smooth stone, and instructs me to hold onto it until the end of the play. The play is The Girl Who Was Raised by Wolverine, written and directed by Deneh’Cho Thompson.

The concept of the play is intriguing. It’s set in the not-too-distant future, when overpopulation and unsustainable development have pushed our planet to its brink; resources are scarce and conditions are bleak. Amid the reigning chaos, military governments have implemented ‘the culling’: a system in which one in three people are killed for the greater good, in order to reduce the human population by a third.

The protagonist, Stephanie, played by Tai Amy Grauman, is in a unique situation. At present, a mutant strain of smallpox is ravaging the wealthy white population, and Stephanie – who has a white mother and Native father – has been quarantined while a serum is derived from her blood. And to thank her for unwittingly providing the smallpox cure, Stephanie is given a special privilege: she gets to choose which of her parents will die in the culling.

The set consists of a few pieces: a pair of curtains, the sort that one would find in a hospital, wheeled between beds in order to give patients privacy; and a stretcher, also wheeled, which constitutes Stephanie’s bed. These clinical items prove very versatile, substituting for various objects and environments while preserving a desolate atmosphere. However, different places – or rather, different times – are established mainly through lighting. Blue marks the cold and stale facility where Stephanie lives; warm, golden light evokes her memories of home. Her mother, played by Jessica Hood, is an overbearing, anxious wreck who had to care for Stephanie alone whenever the father, portrayed by John Cook, was arrested trying to fend for the family – often breaking laws in order to do so. And then, there is one final lighting queue: a fairly neutral tone, which represents the domain of Wolverine.

The play’s summary teases that Stephanie “is isolated and alone – until Wolverine appears”. But from what I can tell, Stephanie and the supernatural figure of Wolverine seem to exist in two different realms; she is in the realm of the linear story, which Wolverine watches from a strangely meta, omniscient vantage point. In fact, Wolverine isn’t mentioned by name in the play. And no, this isn’t Marvel’s star X-Man; this Wolverine appears to be a wise, mischievous spirit, or deity.

Wolverine is a dual entity, played by both Hood and Cook. In fact, aside from Stephanie, Hood and Cook play all characters: Hood also plays Stephanie’s doctor and mother, while Cook plays the prison guard and Stephanie’s father. Throughout the play, the actors suspend the narrative action and become the bipartite Wolverine figure, donning those grey fur articles and breaking the fourth wall, bickering with each other while soliciting the audience’s opinions on how the story ought to proceed.

These asides to the audience are often funny, contrasting with the play’s sombre tone. They infuse the performance with a more spontaneous storytelling element, differentiating it from a typical production. But the trouble is that they may be a bit too disruptive; the narrative loses momentum during these shifts, making them feel less like an immediate engagement with the storyteller, and more like a Brechtian device meant to undermine the play’s believability.

More problematic is the fact that while Hood and Cook are both good actors, their roles haven’t been scripted with enough variation. I don’t see a great big difference between the strict and impatient mother, who seems overwhelmed; the strict and impatient doctor, who seems overworked; and the strict and impatient female aspect of Wolverine, who seems anxious to get the culling over with. On the flip side, it’s hard not to feel for the dad, as he dotingly calls Stephanie ‘Little Feather’; or the guard, who smuggles Stephanie food; or the male aspect of Wolverine, who tries desperately to defer condemning one of Stephanie’s parents to death.

Far from the dualistic spirit of ‘wolverine’, it appears that Stephanie is caught between two opposing forces – ‘protective papa bear’ versus ‘untamed shrew’ – each manifest across three different entities. The similarities in the characters might be intentional; but as an audience member, I don’t want to be depending on lighting queues or costume hints to know when a shift has taken place.

The Girl Who Was Raised By Wolverine’s biggest problem, however, is that its execution doesn’t live up to its promise. In building the play’s detailed world, Thompson touches on numerous imminent issues – resource depletion, overpopulation, and histories of race relations, to name but a few. On paper, this looks intriguing. But these issues are glossed over in the script so entirely that they feel arbitrary. The plot is so narrowly focussed on Stephanie’s impossible choice that all other story elements become utterly irrelevant.

For all intents and purposes, this could be a story about an impoverished household, with the child only scrounging enough morsels to feed herself and one of her dying parents. It could be the end of Hans Christian Andersen’s faerie tale The Mermaid, where the title character must choose between taking an innocent life or living the rest of her life in despair; she resolves the dilemma by killing herself instead. Spoiler warning: The Girl Who Was Raised By Wolverine doesn’t stray far from this trope.

And when Stephanie chooses at the end of the play to sacrifice her own life to save both parents, the decision isn’t surprising. It would be different if her captors were coddling her while drawing blood samples, whisking her out of poverty and into a life of luxury in an effort to keep her complacent. But Stephanie’s unrelenting misery, and her ostensible hatred for her present situation, makes what should be a tragic end of the play feel like an obvious solution.

Between the wry karma of the smallpox outbreak affecting the rich, the inherent hypocrisy of trying to cure society’s infected elites while culling the general population, and themes of natural exploitation and resource mismanagement, I get the sense that The Girl Who Was Raised By Wolverine has bit off more than it can chew. Perhaps a larger cast, or different characters, would’ve helped to convey some of its ideas more fully.

At the end of the performance, we are asked to choose which of Stephanie’s parents we would have sacrificed to the culling. The actors wait at the end of the stage, near the exit, each holding a bucket, into which we’re to drop our stones depending on who we think should be killed. I take a quick glance in passing; the mother’s bucket is much fuller. Sad, yes, but – like many of the plot elements heretofore – unsurprising.

Written by Justin Ramsey

Justin Ramsey holds a Masters in Comparative Media Arts from Simon Fraser University. He works as an arts administrator with various institutions including Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, and Republic Gallery, Vancouver. As a freelance writer, Justin has contributed to several publications and platforms, including MONTECRISTO Magazine and NUVO Magazine.