Choose Your Own Adventure

Isabelle Kirouac’s Together ( ) Apart

Written by Justin Ramsey

Photos provided by Isabelle Kirouac

“Where are you coming from today?”

“What is the purpose of your visit?”

“How long are you planning to stay?”

I’ve been groomed to handle myself with quiet, agreeable compliance at border crossings, and for the first minutes, Isabelle Kirouac’s performance and installation piece Together ( ) Apart is akin to a normal customs interview. I am standing in a small, curtained room before a desk, laden with an assortment of forms and paperwork; a couple other visitors queue in nondescript chairs until a no-nonsense lady, dressed in black and sporting a headset, enters the room, calls them by name, and whisks them away one at a time. The customs officer interviewing me is soft-spoken and professional, notwithstanding that the bright red accents of her outfit seem at odds with her demeanour, and her bra is plainly visible through her blouse. Her questions, however, are fairly normal: I am asked my name, my place of residence, my intention for coming to the performance today; and I answer with frank, though slightly perplexed, honesty.

After all, these are the sorts of questions one expects to be plied with on geopolitical borders: questions that augment restriction and limit access, forcibly invoking the alienism of the visitor. And though such encounters can be annoying—enfeebling at times, outright dehumanizing at others—customs interviews are, essentially, customary: they are a routine practice now intrinsic in our attempts to explore that which is unfamiliar to us. In this sense, we might view international customs as a means of measuring, quantifying, and regulating our experience of the new.

What’s not customary, however, is when the border officer hoists up her skirt, thrusts her leg upon the desk, and begins rotating her foot, outfitted in a flashy carmine-coloured pump.

It is simultaneously unnerving and relieving when this happens. Unnerving because the sharp deviation from predictability unsettles me, somehow inciting a similar sensation to being told that my perfectly valid passport is unacceptable, or that my innocuous luggage is suspicious and will be unpacked by security.

But relieving because the bare leg across the desk is, paradoxically, the antithesis of such bureaucratic authority. Quite oppositely, the gesture robs the customs desk of its power, fundamentally opening the once-mundane experience to an infinity of unexpected possibilities. It is an exciting reminder that no matter how oppressed the border is by monotonous officialdom, it inherently remains a site of discovery, interchange, and liminality.

From here, the proceedings grow stranger:

“Maintain eye contact with me and walk toward me. Please stop when you start to feel uncomfortable.”

“Stand facing away from me at the other end of the room. I’m going to walk towards you. Ring the bell when you think I’m about to touch you.”

I realise that this interrogation no longer concerns a border drawn by politicians on a map, but rather the borders of my own self—borders that I alone enforce and maintain. As I walk toward the attendant, I purposefully do not stop until I have stepped consciously out of my comfort zone; I feel as though I am bearing down on her, staring into her eyes. She pulls out a measuring tape and reveals that there are still eleven inches—almost a whole foot—between us.

Eventually, she announces that we are out of time, presenting me with a contract that I may choose to sign, claiming “responsibility for my own experience.” I find it strange that customs, which strives to track and regulate experience, should now defer this responsibility to me. Still, I sign the contract. After surrendering my personal items—keys, wallet, phone, bag, and even shoes—there is little to do other than to sit down in the dull chair, await the lady with the headset, and watch the next traveller in line attempt to navigate the borders of their own making.

After about ten minutes, the lady in black enters the room, calls my name, and directs me into Studio T at Simon Fraser University’s School for the Contemporary Arts. But far from being the expansive, cavernous auditorium I am accustomed to, Kirouac and her collaborators have arranged lighting and curtains to transform the studio into a labyrinthine series of narrow passages and rooms. It is utterly dark, and the only sounds are haunting, euphonious reverberations—deep and soft, reminiscent of a cello—alongside an occasional tinkering, bell-like peal, recurring throughout the performance. At first, I hover at the entrance, unsure of what to do—there is no didactic guide to direct me—but after a moment’s hesitation I follow the sparse lighting up the corridor, round the corner, and come upon a chair next to a small cassette player and headset. I sit, don the earphones, and push ‘play’.

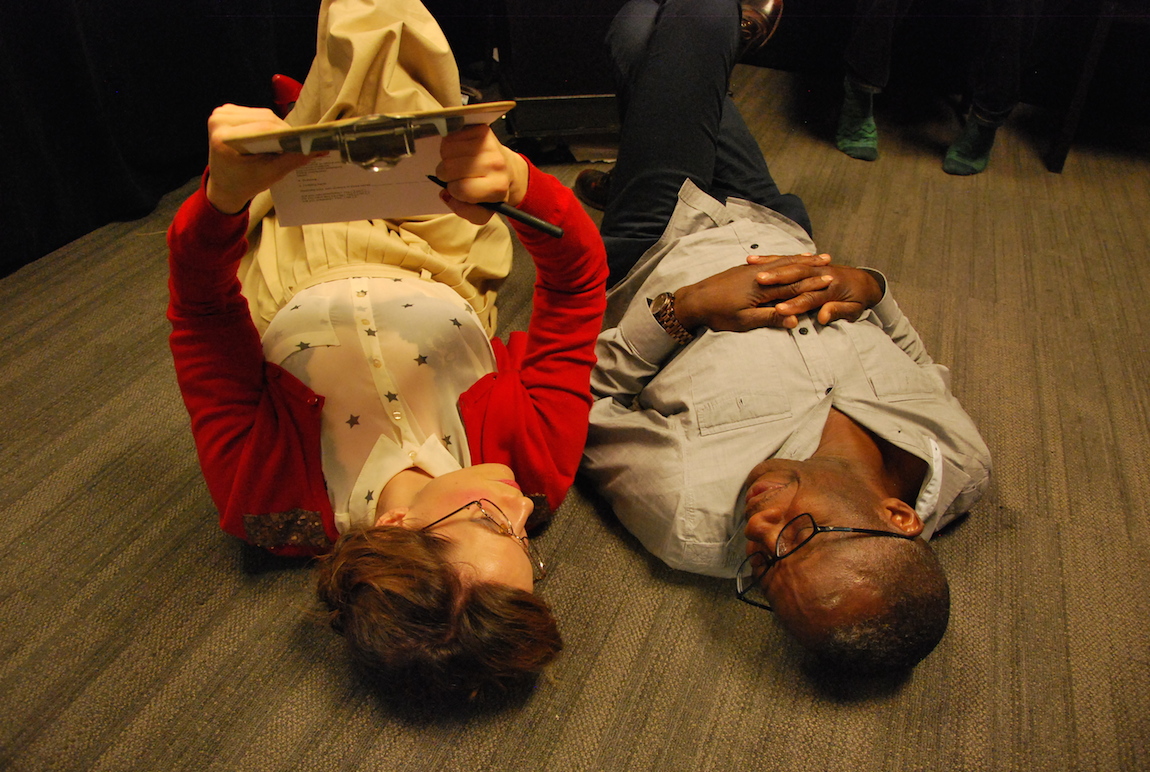

As a female voice ponders the limits of our personal borders—how our bodies unwittingly extend their margins across space, through the travel of our exhaled breath, or the shedding of our dead skin cells—a performer winds and weaves herself between gossamer curtains; the translucent hangings visually reflect these capricious boundaries of flesh and air. “Where does my body end? Where does it begin?” These questions remain with me as the dancer leads me into the next room, where a lady quietly invites me to recline on a mat. Large, smooth stones are strewn about the floor, and a screen suspended overhead scatters green and orange lighting through the small hollow. The milieu has a deeply elemental quality, as though I am in some grotto or grove, or viewing a familiar setting from a radically new perspective; it brings me to wonder how a blade of grass or a mossy pebble might appear to a tinier creature. As the performer lays rocks over my body, between my feet and into my hands, the weight of each draws attention to that place, isolating it. Where does my body begin and end? I am tempted to mention this to the performer, but between her meditative repose and the quietness of the installation, I stay silent. I am, after all, an audience member; I uphold an unspoken hierarchy wherein the artist imparts knowledge and the audience receives it.

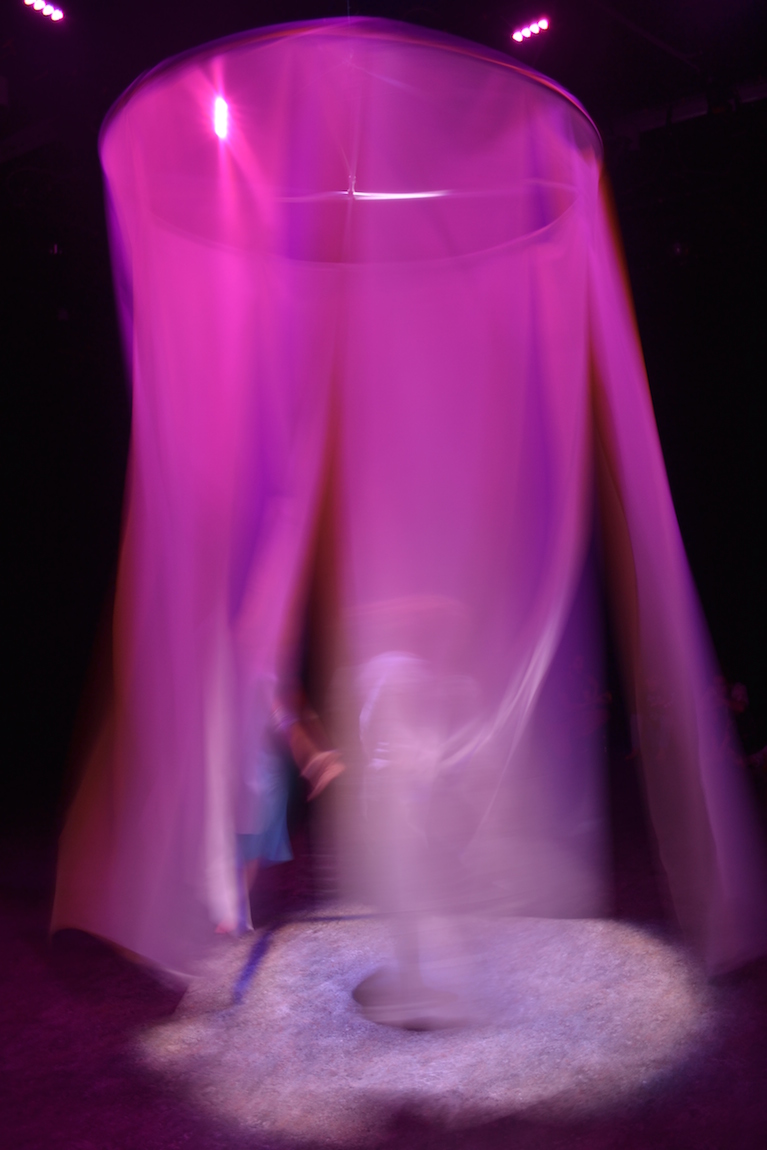

But as she lifts the stones from me one by one, liberation buoys me—I feel an odd sense of freedom. She directs me out into a darkened space; the only light emanates from a circle of white, veil-like curtains hung from a rotary canopy above, at the centre of which is a young woman. Smiling spiritedly, the woman beckons me to join her within the draperies. Dancing jubilantly to music playing from her ear-buds, her golden hair and sparkling eyes form a picture of innocence—and yet, there is something ambiguously medical about this set-up. Perhaps it’s her robin-egg blue dress, or the white surroundings, or the way her mp3 player is strapped to her arm, literally pumping music to animate her, like some behaviour-modifying drug.

And maybe it is because of these iatric connotations that I find her dancing contagious; I allow it to infect me. The stones have been lifted, and I am no longer fettered to passive spectatorship. In an instant, I recall the contract I signed: I assume responsibility for my own experience. So I start to dance as well. We whirl in the curtains, jump, high-five, laugh. I don’t have the benefit of music—even the low, melodious strain from earlier seems to have faded temporarily—but that’s fine. After all, music is, in many ways, a gauge of time: beats, rhythms, measures and time signatures construct a linear temporality that I neither want nor need. In this circle of light, time and space dissolve—and with them, so do my rigorously reinforced frontiers. For a while, I am open.

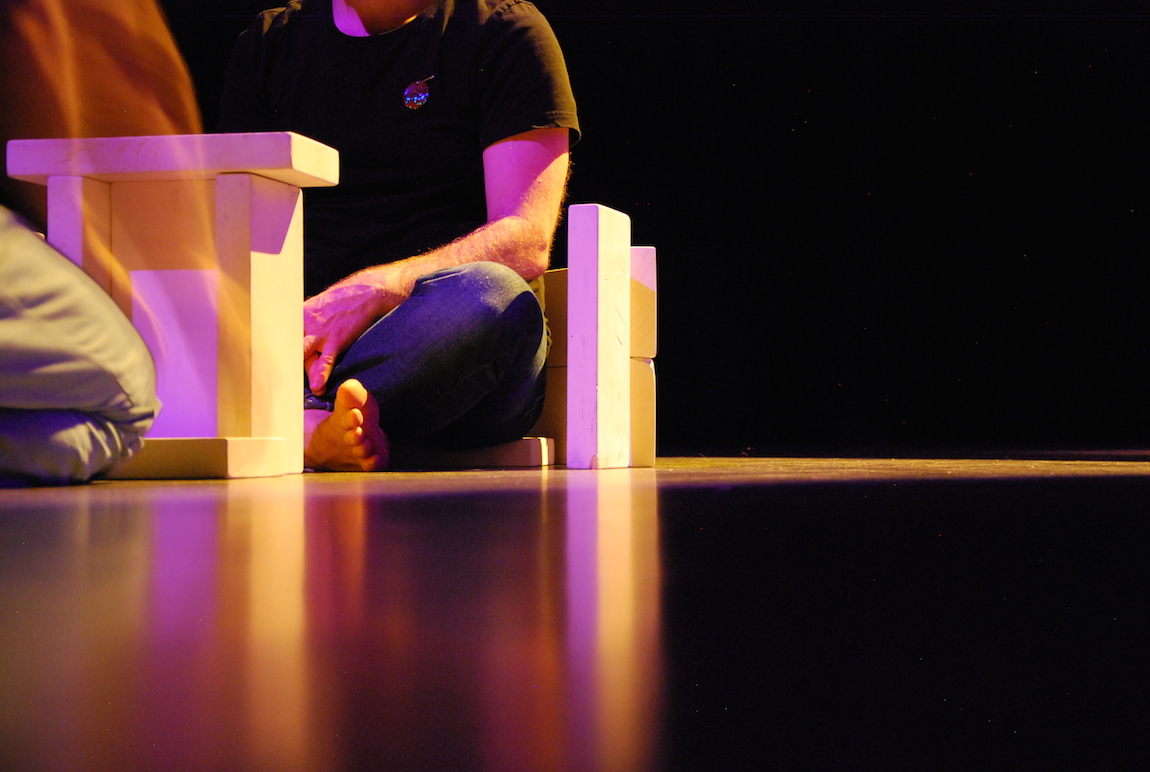

The dancer then points me toward an orange glow that has appeared on the dark floor several feet away, whereupon a man pushes rectangular wooden blocks across the floor. Emboldened by my previous encounter, I join him. We devise unspoken games, forming patterns and arrangements with the blocks, sliding them across the floor in an impromptu sport like boules or curling, and then walking over them as though they were cobblestones. The playfulness continues in the next zone, too. I sit at a computer, beneath an intense spotlight, and I can see through the webcam that I am being projected onto curtains in another room, wherein a dancer reacts to my massive image. I gesture, and she improvises movement in response. Using a sheet of tinfoil, red and blue lighting gels, and a magnifying glass, I can flicker, refract, blend and bend the light and colour in her space; I am curious to see how she adapts, and even retaliates, to my machinations.

Forging ahead, the following area is revealed to be the source of the phantasmal music heard earlier—but it is not played on any cello. Rather, the musician runs a bow over what resembles a series of microphone stands, each of which has a thick, vertical cord running its length that produces a resonant note when struck. The tones vary, but the sound is consistently thick, melancholic and beautiful; it’s peculiarly synaesthetic amid the dark space and crimson lighting. At the centre of the room, two chairs flank a table, on which sits a small, metal device; this too is an instrument. Nevertheless, in my newfound adventurous state, I deliberately avoid such furnishings. I am an emancipated spectator, unwilling to relapse into simply sitting and listening. I join the musician at the far end of the room among the standing instruments. He beams at me, as though intuiting my curiosity, and offers me a bow of my own.

And so begins our duet: we strum and pluck the chords, which thunder with dark, concise vibrations; we draw the bows over them to generate lush and lifting harmonies. It is impossible not to feel the music; it runs up through my feet and around in my bones, and as I stare outward into my scarlet surroundings I could easily be gazing inward, following the timbre’s trajectory as it passes through me. Our song reaches a natural conclusion, and I am directed out into one final passageway.

It’s a waiting room similar to the first one, except there are no people—just a few chairs and a small monitor. As ought to be expected in any customs office, a security camera had been filming me earlier, and the footage of my interrogation is presently playing back. Specifically, it is the exact moment when I was turned away from the officer with the bell in hand, instructed to ring it when I suspected she was about to touch me. I remember standing there, feeling maddeningly antsy and uncomfortable, certain that she was approaching swiftly. How embarrassing, then, to realize that she had barely advanced a couple of feet before I rang the bell.

As I chuckle at myself from 70 minutes ago, I wonder if I would have waited longer—been more trusting, more curious, less afraid—if I tried the same exercise now. I’d like to think so.

Justin Ramsey holds a Masters in Comparative Media Arts from Simon Fraser University. He works as an arts administrator with various institutions including Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, and Republic Gallery, Vancouver. As a freelance writer, Justin has contributed to several publications and platforms, including MONTECRISTO Magazine and NUVO Magazine.